Cargando

Eleven days before signing its sale in June 2011 to Cargill, a US corporation, poultry producer Pipasa - then controlled by Grupo Empresarial Sama S.A. - established an offshore corporation in Panama to close the deal, which amounted to $12 million. Cargill did the same, though two months earlier.

The amount of the takeover merger and the legal intricacies which made it possible are only now being disclosed, five years after the deal was settled, thanks to secret files obtained by the German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung, shared with the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ), DataBaseAR, the research unit at AmeliaRueda.com - and more than 100 media partners around the world, as part of the largest global investigation in history.

The more than 11 million files, dating from 1977 to December 2015, uncover the inner workings of Mossack Fonseca & Co., a global law firm based in Panama with offices around the world, specialized in creating offshore shelters for its customers; they also reveal connections between companies and individuals that purchased their services.

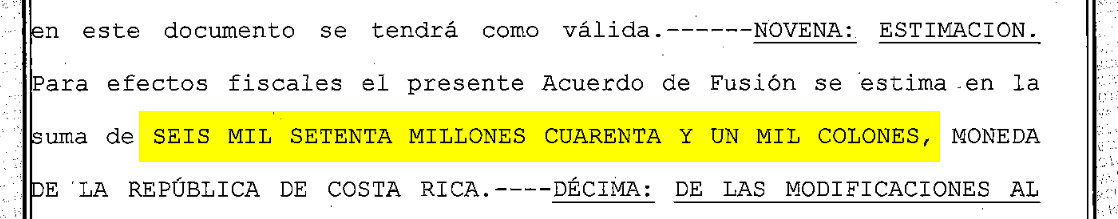

“For tax purposes this Merger Agreement is estimated at the sum of six point zero seven billion colones, currency of the Republic of Costa Rica,” states the ninth clause of the agreement.

These ¢6.07 billion are equivalent to $12 million at the exchange rate of the time and according to a certification by the National Bank of Panama, included in the leaked files.

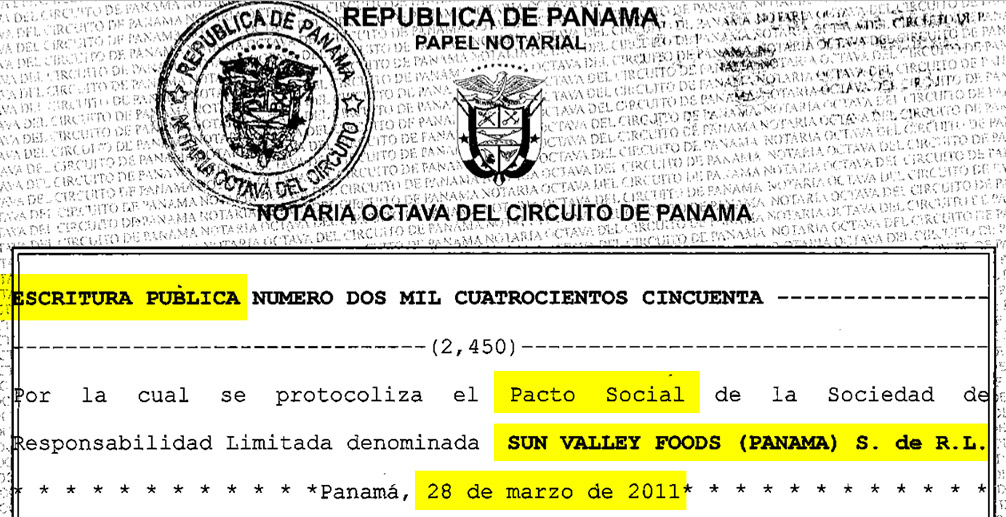

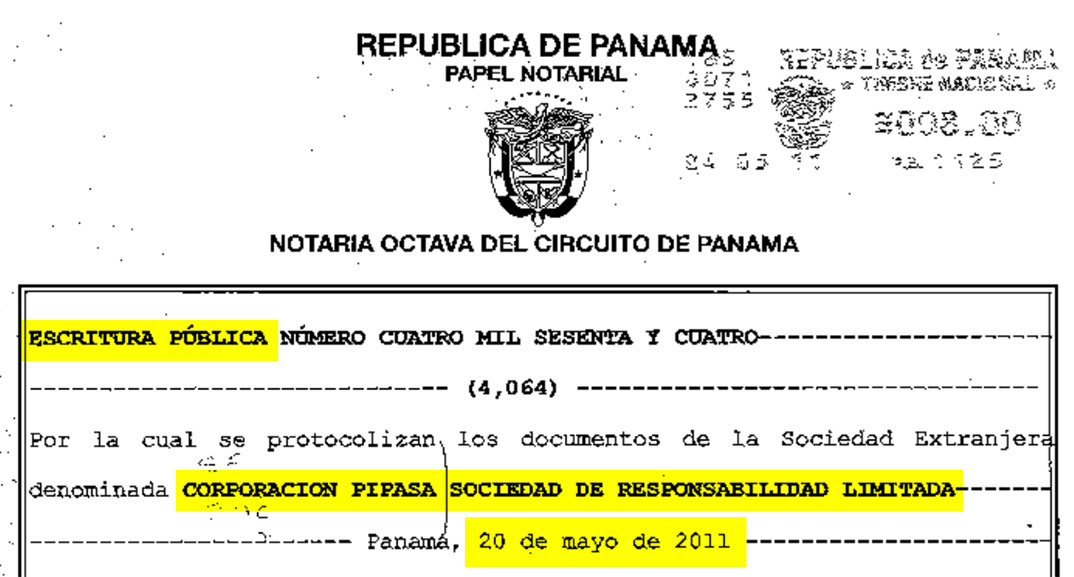

The files expose that, in order to sign the merger in Panama, Pipasa registered Corporación Pipasa Sociedad de Responsabilidad Limitada on May 20, 2011 in Panama, under book 2011, entry 91688. Cargill, in turn, incorporated the limited liability company Sun Valley Foods (Panama) S de R.L. on March 28, 2011 under book 2011, entry 58171.

The registered agent for both companies at Panama’s Public Registry was Mossack Fonseca, as Panama’s laws require all legal entities to have an agent (lawyer or law firm) registered in the country. The Panamanian firm also handled all other legal paperwork before and after the merger, and the agreement was signed by the parties on June 1, 2011.

As a result of the merger, Corporación Pipasa Sociedad de Responsabilidad Limitada prevailed, and Sun Valley Foods (Panama) S de R.L. disappeared.

From Costa Rica, the law firm that served as liaison between Pipasa and Mossack Fonseca was Lara, López, Matamoros, Rodríguez & Tinoco (LLMR & T), client number 11653 of the Panamanian offshore services provider.

Signing the agreement on behalf of Cargill was Venezuelan lawyer, Nathalie Torres Marquéz, and for Pipasa, Costa Rican businessman Víctor Oconitrillo Conejo, then chairman of board of Rica Foods Incorporated, which controlled the Costa Rican corporation’s capital stock before the merger, and CEO of Grupo Empresarial Sama S.A., owner of Rica Foods’ shares.

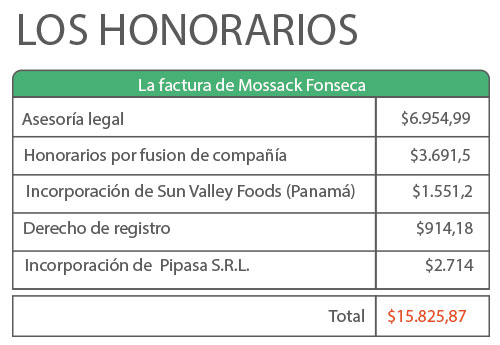

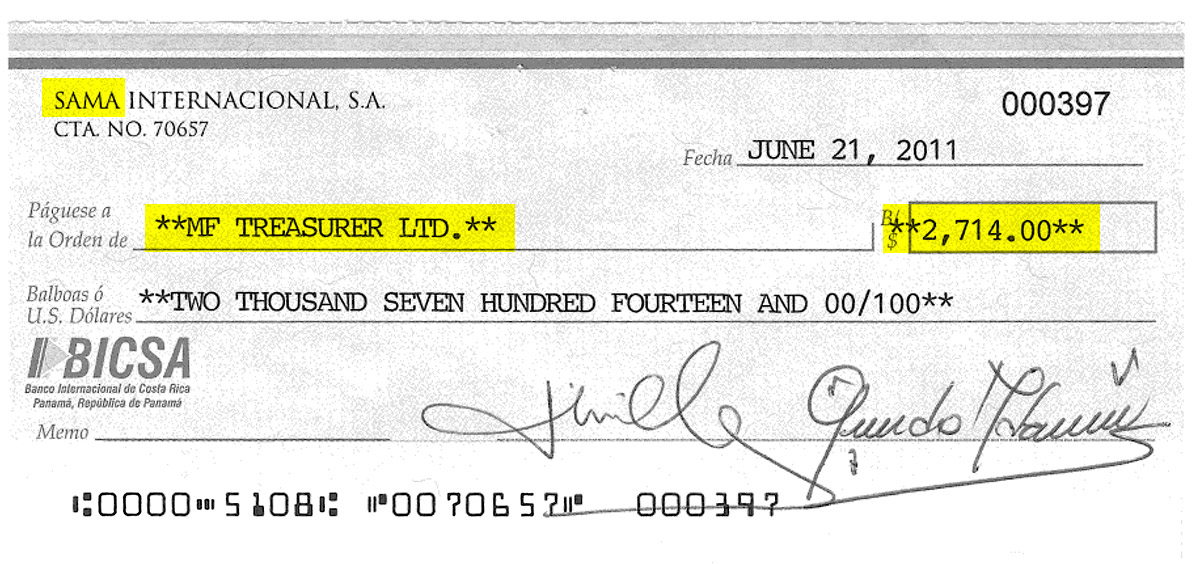

As evidenced by the invoices issued by Mossack Fonseca, the parties paid a total $15,825.87 for the various services involved in the transaction: legal advisory provided by Mossack Fonseca ($6,954.99); fees for merger of companies ($3,691.5); incorporation fees for Sun Valley Foods (Panama) S de R.L.; annual charges for corporations and others ($1,551.2); amendment of social pact of Sun Valley Foods (Panama) and expedite registration rights ($914.18); and incorporation fees for Corporación Pipasa Sociedad de Responsabilidad Limitada, among others ($2,714).

Grupo Sama paid Mossack Fonseca the amount corresponding to Pipasa’s incorporation in Panama on June 21, 2011 with check number 397 of Banco Internacional de Costa Rica (BICSA), a copy of which is included in the secret documents.

“This deal is ruled by a confidentiality agreement among the parties, which does not allow providing any information,” stated Gerardo Matamoros, Sama corporate director, in response to queries by DataBaseAR.

In the United States of America (USA), as a private company, Cargill reports its financial results on a quarterly basis. However, it has the possibility of suppressing a series of figures, such as those referring to acquisitions or sales.

“Our company’s practice is not to make public any details of private transactions,” Cargill answered in writing.

Neither Costa Rican nor US tax authorities are authorized to disclose information on their taxpayers’ tax returns.

Article 117 of the Code of Tax Rules and Procedures of Costa Rica protects as confidential any information obtained by the Tax Administration from its taxpayers. Tax Administration officials cannot disclose, in any way, the amount or source of income, or any other data included in the tax returns.

In the US, “federal law prohibits us from commenting on specific individual or corporate taxpayers,” was the answer received by DataBaseAR from the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), responsible for tax collection and compliance with the tax laws of the United States.

These impediments prevent them from disclosing how, and if, in 2011 the sale of Pipasa was declared to Costa Rican tax authorities, or its purchase to the IRS.

In Costa Rica, however, the Income Tax Law, under Article 6, excludes tax payment on capital gains obtained when transferring movable and immovable goods.

Moreover, the statute of limitations on any action by the Costa Rican tax authorities demanding payment of taxes and interest - should the deal be subject to this - prescribed in 2014. Since 2012, the limitation period went from three to four years.

The Tax Administration argues that it is precisely in order to have evidence of the fiscal risks potentially generated in similar transactions that it is pushing the Legislative Assembly to create a register of shareholders in the bill of the Law against Tax Fraud.

“We could determine who is actually behind these flows of money and determine relevant risk evidence or analysis,” said the director general of Taxation, Carlos Vargas.